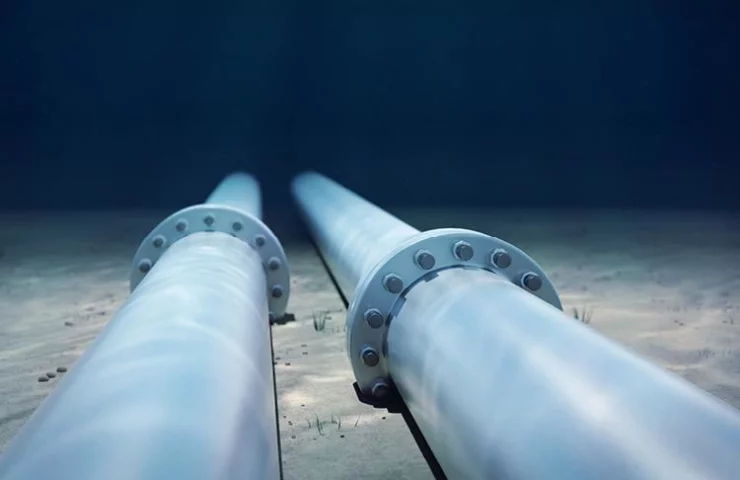

According to German researchers at the Technical University of Munich, not only supply bottlenecks, as they are now, can lead to a shortage of natural gas or oil. Under certain conditions, the mixture in pipelines, usually consisting of gas, oil and water, can become very viscous and even form solid phases.

Particularly big problems for operators are solid hydrates formed from gas and water, for example, when the mixture cools to low seabed temperatures during long shutdowns of the pipeline.

In order to clear the blockage in situ, you first need to find the damaged section of the pipeline. Localization of blockages from the outside is a difficult task, since they can form anywhere along the length of the pipeline.

Today, thermal imaging cameras and gamma radiation are used to detect blockages. However, none of these methods work underwater. Ultrasound, on the other hand, penetrates water without problems, but hydrate blocks can only be detected at a close distance outside the pipe wall.

This limitation creates practical difficulties as subsea pipelines are laid at depths of up to 2,000 meters and are often naturally covered by seabed materials such as sand or silt. Another technical problem associated with acoustic methods arises from the lack of a clear difference between the acoustic impedances of the hydrate phase and other phases of the crude oil mixture, making it difficult to distinguish.

According to Dr. Sophie Bouat, "Neutrons are the perfect probe for this task." She established contact with scientists at the Heinz Mayer-Leibniz Center in Garching near Munich.

“Using activation gamma-neutron analysis, you can very accurately detect light atoms and, in particular, hydrogen,” she continues. Since the hydrogen content of hydrates and conventional oil or gas differ significantly, it should be possible to detect plugging by measuring the hydrogen concentration.

Dr. Ralf Gilles, industry coordinator of the FRM II Research Neutron Source, conducted a feasibility study on this topic together with other colleagues from the Technical University of Munich and the Jülich Research Centre. Using a PGAA (Gamma Ray Fast Activation Analysis) instrument that uses cold neutrons from FRM II, the researchers determined that this approach can be used to differentiate between oil and gas and plugging.

On the NECTAR radiography and tomography facility and the FaNGAS (fast neutron gamma ray spectroscopy) instrument, they used fast neutrons from the FRM II to show that enough neutrons penetrate the metal walls of pipelines to facilitate appropriate measurements, and that measurement also works well underwater.

“The results clearly demonstrate that neutrons are ideal for this application. Moreover, experiments have shown that we can distinguish even a nascent blockage from a fully developed blockage,” says Dr. Ralph Gilles. “This is very useful, because then you can even preemptively heat a segment of the pipe to melt the blockage before it fully develops.”

In practice, a mobile detector with a small neutron source will move back and forth through the pipeline looking for blockages.

In addition to scientists from the Technical University of Munich, researchers from Forschungszentrum Jülich and RWTH Aachen University took part in the analysis.