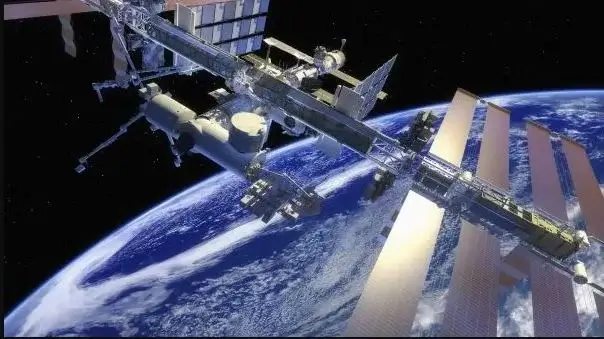

Early Tuesday morning (November 16), the International Space Station (ISS) crew of seven woke up in alarm. During the tests of the Russian rocket, the newly decommissioned Cosmos satellite (Cosmos) shattered into more than 1,500 pieces of space debris, some of which were close enough to the ISS, which required preparation for an emergency collision.

According to NASA, four Americans, one German and two Russian astronauts aboard the station were ordered to hide in the transport capsules that took them to the ISS, while the station passed the debris cloud several times.

In the end, Tuesday ended with no reports of damage or injury aboard the ISS, but the crew's precautions - and NASA's stern response to Russia - were far from overreacting. Space debris like that generated by the destruction of Cosmos can travel at more than 17,500 miles per hour (28,000 km /h), NASA says, and even a pea-sized piece of metal could become a potentially deadly rocket. in low orbit conditions. (By comparison, a typical bullet fired from an AR-15 rifle travels at just over 2,200 mph or 3,500 km /h.)

“It doesn't take a very big hole to blow up a space station,” said John Crassidis, Professor Emeritus of SUNY at the University of Buffalo in New York, who is working with NASA to monitor space debris.

Indeed, a hole just 0.5 inches (1.3 centimeters) wide could cause irreparable structural damage that could wipe out the space station entirely, Crassidis said.

This is a serious concern, Crassidis said, as the amount of orbital debris - or "space debris" - around the Earth has grown exponentially over the past 60 years. NASA is currently tracking over 27,000 large debris in orbit and is using computer models to estimate the position of millions of smaller pieces of debris that are too small to be seen.

According to Crassidis, if a piece of space debris has a greater than 1 in 10,000 chance of colliding with a passing satellite or spacecraft, NASA uses evasive maneuvers to physically remove the threatened ship. He added that this is a tricky balance, as moving a satellite out of the path of one piece of debris could inadvertently send it into the path of another piece of debris — such is the scale of the mess.

Since 1999, the ISS has changed course 25 times to avoid known debris. According to NASA, to protect the station from smaller debris, the spacecraft is covered with more than 100 shockproof shields, known as Whipple Shields, which serve as “sacrificial bumpers” to receive incoming impacts instead of the ISS wall.

Multiple dents on the outside of the ISS indicate that debris has previously entered the station. In June 2021, debris even blew a hole in one of the station's manipulators, a metal apparatus only 14 inches (35 cm) in diameter. Fortunately, the damage was very minor and the equipment resumed operation immediately.

However, if the ISS itself is well protected from the approaching small debris, the astronauts who maintain it are not protected - and this is the biggest risk. According to Crassidis, even a collision with the smallest piece of orbital debris could instantly kill an astronaut working outside the ISS during a spacewalk. "Space suits are not protected at all," Crassidis said. “Imagine that a ball is flying at you at a speed of 17,000 miles per hour (27,000 km /h) - it will pierce you like a bullet.”

Unfortunately, added Krassidis, there are no international laws prohibiting countries from testing missiles in low orbit, such as the one Russia has just conducted. He fears that the astronaut could be seriously injured or even killed before the world takes the issue of space debris seriously.

While the immediate danger to the ISS from the Russian rocket test is now over, the debris from the explosion could remain dangerous for many or even decades, said Tim Florer, head of the European Space Agency's (ESA) Space Debris Administration. Satellites will almost certainly have to take evasive measures to stay clear of the debris cloud, and the ISS continues to pass it every 90 minutes. "NASA will keep an eye on the debris cloud as closely as possible," Crassidis said.